Death Valley National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Death Valley National Park is an American

According to the

According to the  The highest range within the park is the Panamint Range, with

The highest range within the park is the Panamint Range, with  The hot, dry climate makes it difficult for soil to form.

The hot, dry climate makes it difficult for soil to form.

The ores that are most famously associated with the area were also the easiest to collect and the most profitable: evaporite deposits such as salts,

The ores that are most famously associated with the area were also the easiest to collect and the most profitable: evaporite deposits such as salts,  The teams averaged two miles (3 km) an hour and required about 30 days to complete a round trip. The trade name ''20-Mule Team Borax'' was established by

The teams averaged two miles (3 km) an hour and required about 30 days to complete a round trip. The trade name ''20-Mule Team Borax'' was established by

Soon the valley was a popular winter destination. Other facilities started off as private getaways but were later opened to the public. Most notable among these was Death Valley Ranch, better known as

Soon the valley was a popular winter destination. Other facilities started off as private getaways but were later opened to the public. Most notable among these was Death Valley Ranch, better known as

The

The

The park has a diverse and complex geologic history. Since its formation, the area that comprises the park has experienced at least four major periods of extensive

The park has a diverse and complex geologic history. Since its formation, the area that comprises the park has experienced at least four major periods of extensive

A

A

In the early-to-mid-

In the early-to-mid-

The ancestors of the

The ancestors of the

There are nine designated campgrounds within the park, and overnight backcountry camping permits are available at the Visitor Center.

There are nine designated campgrounds within the park, and overnight backcountry camping permits are available at the Visitor Center.

* * * * * (adapted public domain text) * Rothman, Hal K., and Char Miller. ''Death Valley National Park: A History'' (University of Nevada Press; 2013) 216 pages; an environmental and human history * * (adapted public domain text) * * *

Death Valley National Park

by the

1920s images of Death Valley and Surrounding Locales from the Death Valley Region Photographs Digital Collection

Utah State University

Death Valley National Park

by the Death Valley Conservancy {{authority control National parks in California Protected areas of the Mojave Desert Protected areas of the Great Basin Sandboarding locations Parks in San Bernardino County, California National parks in Nevada Protected areas of Nye County, Nevada Protected areas of Esmeralda County, Nevada Protected areas established in 1994 Civilian Conservation Corps in California Parks in Southern California Dark-sky preserves in the United States 1994 establishments in California 1994 establishments in Nevada

national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

that straddles the California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

–Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

border, east of the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

. The park boundaries include Death Valley

Death Valley is a desert valley in Eastern California, in the northern Mojave Desert, bordering the Great Basin Desert. During summer, it is the Highest temperature recorded on Earth, hottest place on Earth.

Death Valley's Badwater Basin is the ...

, the northern section of Panamint Valley

The Panamint Valley is a long basin located east of the Argus and Slate ranges, and west of the Panamint Range in the northeastern reach of the Mojave Desert, in eastern California, United States.

Geography

The northern end of the valley is in ...

, the southern section of Eureka Valley and most of Saline Valley

Saline Valley is a large, deep, and arid graben, about in length, in the northern Mojave Desert of California, a narrow, northwest–southeast-trending tectonic sink defined by fault-block mountains. Most of it became a part of Death Valley Natio ...

. The park occupies an interface zone between the arid Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

and Mojave deserts, protecting the northwest corner of the Mojave Desert and its diverse environment of salt-flats, sand dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, f ...

s, badlands

Badlands are a type of dry terrain where softer sedimentary rocks and clay-rich soils have been extensively eroded."Badlands" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 2, p. 47. They are characterized by steep slopes, m ...

, valleys, canyons and mountains. Death Valley is the largest national park in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

, as well as the hottest, driest and lowest of all the national parks in the United States. It contains Badwater Basin

Badwater Basin is an endorheic basin in Death Valley National Park, Death Valley, Inyo County, California, noted as the lowest point in North America and the United States, with a depth of below sea level. Mount Whitney, the highest poi ...

, the second-lowest point in the Western Hemisphere and lowest in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

at below sea level. More than 93% of the park is a designated wilderness area

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

. The park is home to many species of plants and animals that have adapted to this harsh desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

environment including creosote bush

''Larrea tridentata'', called creosote bush and greasewood as a plant, chaparral as a medicinal herb, and ''gobernadora'' (Spanish for "governess") in Mexico, due to its ability to secure more water by inhibiting the growth of nearby plants. In S ...

, Joshua tree

''Yucca brevifolia'' is a plant species belonging to the genus ''Yucca''. It is tree-like in habit, which is reflected in its common names: Joshua tree, yucca palm, tree yucca, and palm tree yucca.

This monocotyledonous tree is native to the ar ...

, bighorn sheep

The bighorn sheep (''Ovis canadensis'') is a species of sheep native to North America. It is named for its large horns. A pair of horns might weigh up to ; the sheep typically weigh up to . Recent genetic testing indicates three distinct subspec ...

, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecologica ...

, and the endangered Death Valley pupfish

The Death Valley pupfish (''Cyprinodon salinus''), also known as Salt Creek pupfish, is a small species of fish in the family Cyprinodontidae found only in Death Valley National Park, California, United States. There are two recognized subspec ...

, a survivor from much wetter times. UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

included Death Valley as the principal feature of its Mojave and Colorado Deserts Biosphere Reserve The Mojave and Colorado Deserts Biosphere Reserve is a biosphere reserve designated by UNESCO in 1984 to promote the ecological conservation of a cluster of areas in the Mojave and Colorado deserts of California. A principal feature is Death Valle ...

in 1984.

A series of Native American groups inhabited the area from as early as 7000 BC, most recently the Timbisha

The Timbisha ("rock paint", Timbisha language: Nümü Tümpisattsi) are a Native American tribe federally recognized as the Death Valley Timbisha Shoshone Band of California. They are known as the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe and are located in sout ...

around 1000 AD who migrated between winter camps in the valleys and summer grounds in the mountains. A group of European Americans, trapped in the valley in 1849 while looking for a shortcut to the gold fields of California, gave the valley its name, even though only one of their group died there. Several short-lived boom town

A boomtown is a community that undergoes sudden and rapid population and economic growth, or that is started from scratch. The growth is normally attributed to the nearby discovery of a precious resource such as gold, silver, or oil, although ...

s sprang up during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to mine gold and silver. The only long-term profitable ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 Apr ...

to be mined was borax

Borax is a salt ( ionic compound), a hydrated borate of sodium, with chemical formula often written . It is a colorless crystalline solid, that dissolves in water to make a basic solution. It is commonly available in powder or granular for ...

, which was transported out of the valley with twenty-mule team

Twenty-mule teams were teams of eighteen mules and two horses attached to large wagons that transported borax out of Death Valley from 1883 to 1889. They traveled from mines across the Mojave Desert to the nearest railroad spur, away in Moja ...

s. The valley later became the subject of books, radio programs, television series, and movies. Tourism expanded in the 1920s when resorts were built around Stovepipe Wells

Stovepipe Wells is a way-station in the northern part of Death Valley, in unincorporated Inyo County, California.

Geography and names

Stovepipe Wells is located at and is US Geological Survey (USGS) feature ID 235564. It is entirely inside Deat ...

and Furnace Creek. Death Valley National Monument was declared in 1933 and the park was substantially expanded and became a national park in 1994. National Park Index (2001–2003), p. 26

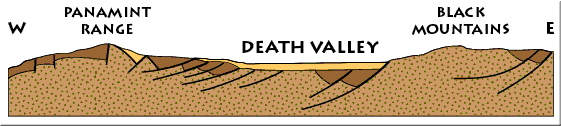

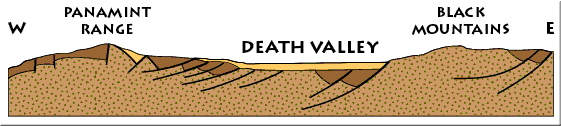

The natural environment of the area has been shaped largely by its geology. The valley is actually a graben

In geology, a graben () is a depressed block of the crust of a planet or moon, bordered by parallel normal faults.

Etymology

''Graben'' is a loan word from German, meaning 'ditch' or 'trench'. The word was first used in the geologic contex ...

with the oldest rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

s being extensively metamorphosed

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock (protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, causi ...

and at least 1.7 billion years old. Ancient, warm, shallow seas deposited marine sediments until rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

ing opened the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. Additional sedimentation occurred until a subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

zone formed off the coast. The subduction uplifted

''Uplifted'' is the second studio album by Nigerian singer Flavour N'abania. It was released on July 20, 2010, by Obaino Music and 2nite Entertainment. The album features guest appearances from Jay Dey, Oloye, Stormrex, Waga Gee, Asemstone, M-Jay, ...

the region out of the sea and created a line of volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es. Later the crust started to pull apart, creating the current Basin and Range

Basin and range topography is characterized by alternating parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is a result of crustal extension due to mantle upwelling, gravitational collapse, crustal thickening, or relaxation of confining stresses. The e ...

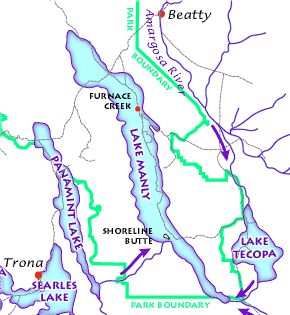

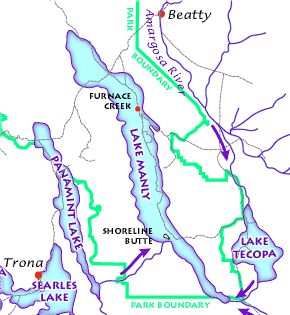

landform. Valleys filled with sediment and, during the wet times of glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

s, with lakes, such as Lake Manly

Lake Manly was a pluvial lake in Death Valley, California, covering much of Death Valley with a surface area of during the so-called "Blackwelder stand". Water levels varied through its history, and the chronology is further complicated by act ...

.

Death Valley is the fifth-largest American national park and the largest in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

. It is also larger than the states of Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

and Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

combined, and nearly as large as Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

. In 2013, Death Valley National Park was designated as a dark sky park

A dark-sky preserve (DSP) is an area, usually surrounding a park or observatory, that restricts artificial light pollution. The purpose of the dark-sky movement is generally to promote astronomy. However, astronomy is certainly not the only obje ...

by the International Dark-Sky Association.

Geographic setting

There are two major valleys in the park,Death Valley

Death Valley is a desert valley in Eastern California, in the northern Mojave Desert, bordering the Great Basin Desert. During summer, it is the Highest temperature recorded on Earth, hottest place on Earth.

Death Valley's Badwater Basin is the ...

and Panamint Valley

The Panamint Valley is a long basin located east of the Argus and Slate ranges, and west of the Panamint Range in the northeastern reach of the Mojave Desert, in eastern California, United States.

Geography

The northern end of the valley is in ...

. Both of these valleys were formed within the last few million years and both are bounded by north–south-trending mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

s. These and adjacent valleys follow the general trend of Basin and Range topography

Basin and range topography is characterized by alternating parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is a result of crustal extension due to mantle upwelling, gravitational collapse, crustal thickening, or relaxation of confining stresses. The e ...

with one modification: there are parallel strike-slip fault

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectonic ...

s that perpendicularly bound the central extent of Death Valley. The result of this shearing action is additional extension in the central part of Death Valley which causes a slight widening and more subsidence there.

Uplift of surrounding mountain ranges and subsidence of the valley floor are both occurring. The uplift on the Black Mountains is so fast that the alluvial fan

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to semiarid climates, but a ...

s (fan-shaped deposits at the mouth of canyons) there are small and steep compared to the huge alluvial fans coming off the Panamint Range

The Panamint Range is a short rugged fault-block mountain range in the northern Mojave Desert, within Death Valley National Park in Inyo County, eastern California. Dr. Darwin French is credited as applying the term Panamint in 1860 during his s ...

. Fast uplift of a mountain range in an arid environment often does not allow its canyons enough time to cut a classic V-shape all the way down to the stream bed. Instead, a V-shape ends at a slot canyon

A slot canyon is a long, narrow channel or drainageway with sheer rock walls that are typically eroded into either sandstone or other sedimentary rock. A slot canyon has depth-to-width ratios that typically exceed 10:1 over most of its length and ...

halfway down, forming a 'wine glass canyon.' Sediment is deposited on a small and steep alluvial fan.

At below sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

at its lowest point, Badwater Basin on Death Valley's floor is the second-lowest depression in the Western Hemisphere (behind Laguna del Carbón

__NOTOC__

Laguna del Carbón ( Spanish for "coal lagoon") is a salt lake in Corpen Aike Department, Santa Cruz Province, Argentina. This salt lake is located from Puerto San Julián, within the ''Gran Bajo de San Julián'' (Great San Julián Dep ...

in Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

), while Mount Whitney

Mount Whitney (Paiute: Tumanguya; ''Too-man-i-goo-yah'') is the highest mountain in the contiguous United States and the Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of . It is in East–Central California, on the boundary between California's Inyo and Tu ...

, only to the west, rises to and is the tallest mountain in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

. This topographic relief is the greatest elevation gradient in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

and is the terminus point of the Great Basin

The Great Basin is the largest area of contiguous endorheic basin, endorheic watersheds, those with no outlets, in North America. It spans nearly all of Nevada, much of Utah, and portions of California, Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming, and Baja California ...

's southwestern drainage. Although the extreme lack of water in the Great Basin makes this distinction of little current practical use, it does mean that in wetter times the lake that once filled Death Valley (Lake Manly

Lake Manly was a pluvial lake in Death Valley, California, covering much of Death Valley with a surface area of during the so-called "Blackwelder stand". Water levels varied through its history, and the chronology is further complicated by act ...

) was the last stop for water flowing in the region, meaning the water there was saturated in dissolved materials. Thus, the salt pans in Death Valley are among the largest in the world and are rich in minerals, such as borax

Borax is a salt ( ionic compound), a hydrated borate of sodium, with chemical formula often written . It is a colorless crystalline solid, that dissolves in water to make a basic solution. It is commonly available in powder or granular for ...

and various salts and hydrate

In chemistry, a hydrate is a substance that contains water or its constituent elements. The chemical state of the water varies widely between different classes of hydrates, some of which were so labeled before their chemical structure was understo ...

s. The largest salt pan in the park extends from the Ashford Mill Site to the Salt Creek Hills, covering some of the valley floor.Badwater, the Devils Golf Course, and Salt Creek are all part of the Death Valley Saltpan. The best known playa in the park is the Racetrack

A race track (racetrack, racing track or racing circuit) is a facility built for racing of vehicles, athletes, or animals (e.g. horse racing or greyhound racing). A race track also may feature grandstands or concourses. Race tracks are also u ...

, known for its moving rocks.

Climate

Köppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, notabl ...

system, Death Valley National Park has a hot desert climate (''BWh''). The plant hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

at Badwater Basin is 9b with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of 28.0 °F (–2.2 °C).

Death Valley is the hottest and driest place in North America due to its lack of surface water and low relief. It is so frequently the hottest spot in the United States that many tabulations of the highest daily temperatures in the country omit Death Valley as a matter of course.

On the afternoon of July 10, 1913, the United States Weather Bureau

The National Weather Service (NWS) is an agency of the United States federal government that is tasked with providing weather forecasts, warnings of hazardous weather, and other weather-related products to organizations and the public for the ...

recorded a high temperature of 134 °F (56.7 °C) at Greenland Ranch (now Furnace Creek) in Death Valley. This temperature stands as the highest ambient air temperature ever recorded at the surface of the Earth. (A report of a temperature of 58 °C (136.4 °F) recorded in Libya in 1922 was later determined to be inaccurate.) Daily summer temperatures of or greater are common, as well as below freezing nightly temperatures in the winter. July is the hottest month, with an average high of and an average low of . December is the coldest month, with an average high of and an average low of . The record low is . There are an average of 197.3 days annually with highs of or higher and 146.9 days annually with highs of or higher. Freezing temperatures of or lower occur on an average of 8.6 days annually.

Several of the larger Death Valley springs derive their water from a regional aquifer

An aquifer is an underground layer of water-bearing, permeable rock, rock fractures, or unconsolidated materials (gravel, sand, or silt). Groundwater from aquifers can be extracted using a water well. Aquifers vary greatly in their characterist ...

, which extends as far east as southern Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. Much of the water in this aquifer has been there for many thousands of years, since the Pleistocene ice ages, when the climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologic ...

was cooler and wetter. Today's drier climate does not provide enough precipitation to recharge the aquifer at the rate at which water is being withdrawn.

The highest range within the park is the Panamint Range, with

The highest range within the park is the Panamint Range, with Telescope Peak

Telescope Peak is the highest point within Death Valley National Park, in the U.S. state of California. It is also the highest point of the Panamint Range, and lies in Inyo County. From atop this desert mountain one can see for over one hundre ...

being its highest point at . The Death Valley region is a transitional zone in the northernmost part of the Mojave Desert

The Mojave Desert ( ; mov, Hayikwiir Mat'aar; es, Desierto de Mojave) is a desert in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains in the Southwestern United States. It is named for the indigenous Mojave people. It is located primarily in ...

and consists of five mountain ranges removed from the Pacific Ocean. Three of these are significant barriers: the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada () is a mountain range in the Western United States, between the Central Valley of California and the Great Basin. The vast majority of the range lies in the state of California, although the Carson Range spur lies primarily ...

, the Argus Range

The Argus Range is a mountain range located in Inyo County, California, southeast of the town of Darwin, California, Darwin. The range forms the western boundary of Panamint Valley, and the northwestern boundary of Searles Valley. The Coso Range i ...

, and the Panamint Range. Air masses tend to lose moisture as they are forced up over mountain ranges, in what climatologists call a rainshadow effect

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carri ...

.

The exaggerated rain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is carrie ...

effect for the Death Valley area makes it North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

's driest spot, receiving about of rainfall annually at Badwater, and some years fail to register any measurable rainfall. Annual average precipitation varies from overall below sea level to over in the higher mountains that surround the valley. USGS weather When rain does arrive it often does so in intense storms that cause flash flood

A flash flood is a rapid flooding of low-lying areas: washes, rivers, dry lakes and depressions. It may be caused by heavy rain associated with a severe thunderstorm, hurricane, or tropical storm, or by meltwater from ice or snow flowing o ...

s which remodel the landscape and sometimes create very shallow ephemeral lakes.

The hot, dry climate makes it difficult for soil to form.

The hot, dry climate makes it difficult for soil to form. Mass wasting

Mass wasting, also known as mass movement, is a general term for the movement of rock or soil down slopes under the force of gravity. It differs from other processes of erosion in that the debris transported by mass wasting is not entrained in ...

, the down-slope movement of loose rock, is therefore the dominant erosive force in mountainous areas, resulting in "skeletonized" ranges (mountains with very little soil on them). Sand dune

A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, fl ...

s in the park, while famous, are not nearly as widespread as their fame or the dryness of the area may suggest. The Mesquite Flat dune field is the most easily accessible from the paved road just east of Stovepipe Wells in the north-central part of the valley and is primarily made of quartz

Quartz is a hard, crystalline mineral composed of silica (silicon dioxide). The atoms are linked in a continuous framework of SiO4 silicon-oxygen tetrahedra, with each oxygen being shared between two tetrahedra, giving an overall chemical form ...

sand. Another dune field is just to the north but is instead mostly composed of travertine

Travertine ( ) is a form of terrestrial limestone deposited around mineral springs, especially hot springs. It often has a fibrous or concentric appearance and exists in white, tan, cream-colored, and even rusty varieties. It is formed by a p ...

sand. The highest dunes in the park, and some of the highest in North America, are located in the Eureka Valley about to the north of Stovepipe Wells, while the Panamint Valley

The Panamint Valley is a long basin located east of the Argus and Slate ranges, and west of the Panamint Range in the northeastern reach of the Mojave Desert, in eastern California, United States.

Geography

The northern end of the valley is in ...

dunes and the Saline Valley

Saline Valley is a large, deep, and arid graben, about in length, in the northern Mojave Desert of California, a narrow, northwest–southeast-trending tectonic sink defined by fault-block mountains. Most of it became a part of Death Valley Natio ...

dunes are located west and northwest of the town, respectively. The Ibex dune field is near the seldom-visited Ibex Hill in the southernmost part of the park, just south of the Saratoga Springs marshland. All the latter four dune fields are accessible only via unpaved roads. Prevailing winds in the winter come from the north, and prevailing winds in the summer come from the south. Thus, the overall position of the dune fields remains more or less fixed.

There are rare exceptions to the dry nature of the area. In 2005, an unusually wet winter created a 'lake' in the Badwater Basin and led to the greatest wildflower season in the park's history. In October 2015, a "1000 year flood event" with over three inches of rain caused major damage in Death Valley National Park. A similar widespread storm in August 2022 damaged pavement and deposited debris on nearly every road, trapping 1,000 residents and visitors overnight.

Human history

Early inhabitants and transient populations

Four Native American cultures are known to have lived in the area during the last 10,000 years. The first known group, the Nevares Spring People, werehunters and gatherers

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

who arrived in the area perhaps 9,000 years ago (7000 BC) when there were still small lakes in Death Valley and neighboring Panamint Valley. A much milder climate persisted at that time, and large game animals were still plentiful. By 5,000 years ago (3000 BC) the Mesquite Flat People displaced the Nevares Spring People. Around 2,000 years ago the Saratoga Spring People moved into the area, which by then was probably already a hot, dry desert.The last known lake to exist in Death Valley likely dried up 3,000 years ago. This culture was more advanced at hunting and gathering and was skillful at handcrafts. They also left mysterious stone patterns in the valley.

One thousand years ago, the nomadic Timbisha

The Timbisha ("rock paint", Timbisha language: Nümü Tümpisattsi) are a Native American tribe federally recognized as the Death Valley Timbisha Shoshone Band of California. They are known as the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe and are located in sout ...

(formerly called Shoshone and also known as Panamint or Koso) moved into the area and hunted game and gathered mesquite

Mesquite is a common name for several plants in the genus ''Prosopis'', which contains over 40 species of small leguminous trees. They are native to dry areas in the Americas.

They have extremely long roots to seek water from very far under grou ...

beans along with pinyon pine

The pinyon or piñon pine group grows in southwestern North America, especially in New Mexico, Arizona, and Utah. The trees yield edible nuts, which are a staple food of Native Americans, and widely eaten as a snack and as an ingredient in New ...

nuts. Because of the wide altitude differential between the valley bottom and the mountain ridges, especially on the west, the Timbisha practiced a vertical migration pattern. Their winter camps were located near water sources in the valley bottoms. As the spring and summer progressed and the weather warmed, grasses and other plant food sources ripened at progressively higher altitudes. November found them at the very top of the mountain ridges where they harvested pine nuts before moving back to the valley bottom for winter.

The California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

brought the first people of European descent known to visit the immediate area. In December 1849 two groups of California Gold Country

The Gold Country (also known as Mother Lode Country) is a historic region in the northern portion of the U.S. state of California, that is primarily on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. It is famed for the mineral deposits and gold mines ...

-bound travelers with perhaps 100 wagons total stumbled into Death Valley after getting lost on what they thought was a shortcut off the Old Spanish Trail. Called the Bennett-Arcane Party, they were unable to find a pass out of the valley for weeks; they were able to find fresh water at various springs in the area, but were forced to eat several of their oxen to survive. They used the wood of their wagons to cook the meat and make jerky. The place where they did this is today referred to as "Burnt Wagons Camp" and is located near Stovepipe Wells.

After abandoning their wagons, they eventually were able to hike out of the valley. Just after leaving the valley, one of the women in the group turned and said, "Goodbye Death Valley," giving the valley its name. Included in the party was William Lewis Manly

William Lewis Manly (April 6, 1820 – February 5, 1903) was an American pioneer of the mid-19th century. He was first a fur hunter, a guide of westward bound caravans, a seeker of gold, and then a farmer and writer in his later years.

H ...

whose autobiographical book '' Death Valley in '49'' detailed this trek and popularized the area (geologists later named the prehistoric lake that once filled the valley after him).

Boom and bust

The ores that are most famously associated with the area were also the easiest to collect and the most profitable: evaporite deposits such as salts,

The ores that are most famously associated with the area were also the easiest to collect and the most profitable: evaporite deposits such as salts, borate

A borate is any of several boron oxyanions, negative ions consisting of boron and oxygen, such as orthoborate , metaborate , or tetraborate ; or any salt with such anions, such as sodium metaborate, and disodium tetraborate . The name also refe ...

, and talc

Talc, or talcum, is a Clay minerals, clay mineral, composed of hydrated magnesium silicate with the chemical formula Mg3Si4O10(OH)2. Talc in powdered form, often combined with corn starch, is used as baby powder. This mineral is used as a thi ...

. Borax was found by Rosie and Aaron Winters near The Ranch at Death Valley (then called Greenland) in 1881. Later that same year, the Eagle Borax Works became Death Valley's first commercial borax operation. William Tell Coleman

William Tell Coleman (1824–1893) was an American pioneer in the settlement of California.

Early life

William Tell Coleman was born in Cynthiana in Harrison County, Kentucky on February 29, 1824. He was educated at St. Louis University in Mis ...

built the Harmony Borax Works plant and began to process ore in late 1883 or early 1884, continuing until 1888. NPS website, "Mining" This mining and smelting company produced borax to make soap

Soap is a salt of a fatty acid used in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products. In a domestic setting, soaps are surfactants usually used for washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping. In industrial settings, soaps are use ...

and for industrial uses. NPS website, "Twenty Mule Teams" The end product was shipped out of the valley to the Mojave railhead in 10-ton-capacity wagons pulled by "twenty-mule team

Twenty-mule teams were teams of eighteen mules and two horses attached to large wagons that transported borax out of Death Valley from 1883 to 1889. They traveled from mines across the Mojave Desert to the nearest railroad spur, away in Moja ...

s" that were actually teams of 18 mules and two horses each.

The teams averaged two miles (3 km) an hour and required about 30 days to complete a round trip. The trade name ''20-Mule Team Borax'' was established by

The teams averaged two miles (3 km) an hour and required about 30 days to complete a round trip. The trade name ''20-Mule Team Borax'' was established by Francis Marion Smith

Francis Marion Smith (February 2, 1846 – August 27, 1931) (once known nationally and internationally as "Borax Smith" and "The Borax King" ) was an American miner, business magnate and civic builder in the Mojave Desert, the San Francisc ...

's Pacific Coast Borax Company

The Pacific Coast Borax Company (PCB) was a United States mining company founded in 1890 by the American borax magnate Francis Smith, the "Borax King".

History

The roots of the Pacific Coast Borax Company lie in Mineral County, Nevada, east of ...

after Smith acquired Coleman's borax holdings in 1890. A memorable advertising campaign used the wagon's image to promote the Boraxo

20 Mule Team Borax is a brand of cleaner manufactured in the United States by The Dial Corporation, a subsidiary of Henkel.Hildebrand, G. H. (1982) "Borax Pioneer: Francis Marion Smith." San Diego: Howell-North Books. The product primarily co ...

brand of granular hand soap and the Death Valley Days

''Death Valley Days'' is an American old-time radio and television anthology series featuring true accounts of the American Old West, particularly the Death Valley country of southeastern California. Created in 1930 by Ruth Woodman, the program ...

radio and television programs. In 1914, the Death Valley Railroad was built to serve mining operations on the east side of the valley. Mining continued after the collapse of Coleman's empire, and by the late 1920s the area was the world's number one source of borax. Some four to six million years old, the Furnace Creek Formation is the primary source of borate minerals gathered from Death Valley's playas.

Other visitors stayed to prospect for and mine deposits of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

, lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

, and silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

. These sporadic mining ventures were hampered by their remote location and the harsh desert environment. In December 1903, two men from Ballarat were prospecting for silver. NPS website, "People" One was an out-of-work Irish miner named Jack Keane and the other was a one-eyed Basque butcher named Domingo Etcharren. Quite by accident, Keane discovered an immense ledge of free-milling gold by the duo's work site and named the claim the Keane Wonder Mine

The Keane Wonder Mine and mill is an abandoned mining facility located within Death Valley National Park in Inyo County, California. It is located in the Funeral Mountains east of Death Valley and Furnace Creek, California

History

The mine was d ...

. This started a minor and short-lived gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

into the area. The Keane Wonder Mine, along with mines at Rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals (phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The mineral ...

, Skidoo and Harrisburg

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Pennsylvania, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the List of c ...

, were the only ones to extract enough metal ore to make them worthwhile. Outright shams such as Leadfield also occurred, but most ventures quickly ended after a short series of prospecting mines failed to yield evidence of significant ore (these mines now dot the entire area and are a significant hazard to anyone who enters them). The boom towns which sprang up around these mines flourished during the first decade of the 1900s, but soon declined after the Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from ...

.

Early tourism

The first documented tourist facilities in Death Valley were a set of tent houses built in the 1920s where Stovepipe Wells is now located. People flocked to resorts built around natural springs thought to have curative and restorative properties. In 1927, Pacific Coast Borax turned the crew quarters of its Furnace Creek Ranch into a resort, creating the Furnace Creek Inn and resort. NPS website, "Furnace Creek Inn" The spring at Furnace Creek was harnessed to develop the resort, and as the water was diverted, the surroundingmarsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

es and wetland

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The ...

s started to shrink.

Scotty's Castle

Scotty's Castle (also known as Death Valley Ranch) is a two-story Mission Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival style villa located in the Grapevine Mountains of northern Death Valley in Death Valley National Park, California, US. Scotty's Castl ...

. This large ranch home built in the Spanish Revival

The Spanish Colonial Revival Style ( es, Arquitectura neocolonial española) is an architectural stylistic movement arising in the early 20th century based on the Spanish Colonial architecture of the Spanish colonization of the Americas.

In th ...

style became a hotel in the late 1930s and, largely because of the fame of Death Valley Scotty, a tourist attraction. Death Valley Scotty, whose real name was Walter Scott, was a gold miner who pretended to be the owner of "his castle", which he claimed to have built with profits from his gold mine. Neither claim was true, but the real owner, Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

millionaire Albert Mussey Johnson

Albert Mussey Johnson (May 31, 1872 – January 7, 1948), was a millionaire who served for many years as president of the National Life Insurance Company, built Scotty's Castle in Death Valley, and was variously partner, friend, and dupe of ...

, encouraged the myth. When asked by reporters what his connection was to Walter Scott's castle, Johnson replied that he was Mr. Scott's banker.

Protection and later history

PresidentHerbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

proclaimed a national monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spec ...

in and around Death Valley on February 11, 1933, setting aside almost two million acres (8,000 km2) of southeastern California and small parts of Nevada. NPS Visitor Guide

The

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

(CCC) developed infrastructure in Death Valley National Monument during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and on into the early 1940s. The CCC built barracks, graded of roads, installed water and telephone lines, and a total of 76 buildings. Trails in the Panamint Range were built to points of scenic interest, and an adobe

Adobe ( ; ) is a building material made from earth and organic materials. is Spanish for ''mudbrick''. In some English-speaking regions of Spanish heritage, such as the Southwestern United States, the term is used to refer to any kind of e ...

village, laundry and trading post were constructed for the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe. Five campgrounds, restrooms, an airplane landing field and picnic facilities were also built. NPS website, "Civilian Conservation Corps"

The creation of the monument resulted in a temporary closing of the lands to prospecting and mining. However, Death Valley was quickly reopened to mining by Congressional action in June 1933. As improvements in mining technology allowed lower grades of ore to be processed, and new heavy equipment allowed greater amounts of rock to be moved, mining in Death Valley changed. Gone were the days of the "single-blanket, jackass prospector" long associated with the romantic west. Open pit

Open-pit mining, also known as open-cast or open-cut mining and in larger contexts mega-mining, is a surface mining technique of extracting rock or minerals from the earth from an open-air pit, sometimes known as a borrow.

This form of minin ...

and strip mine

Surface mining, including strip mining, open-pit mining and mountaintop removal mining, is a broad category of mining in which soil and rock overlying the mineral deposit (the overburden) are removed, in contrast to underground mining, in whic ...

s scarred the landscape as international mining corporations bought claims in highly visible areas of the national monument. The public outcry that ensued led to greater protection for all national park and monument areas in the United States. In 1976, Congress passed the Mining in the Parks Act, which closed Death Valley National Monument to the filing of new mining claims, banned open-pit mining and required the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

to examine the validity of tens of thousands of pre-1976 mining claims. Mining was allowed to resume on a limited basis in 1980 with stricter environmental standards. The last mine in the park, Billie Mine, closed in 2005.

Death Valley National Monument was designated a biosphere reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

in 1984. On October 31, 1994, the monument was expanded by 1.3 million acres (5,300 km2) and re-designated as a national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

, via congressional passage of the California Desert Protection Act (Public Law 103–433). Consequently, the elevated status for Death Valley made it the largest national park in the contiguous United States

The contiguous United States (officially the conterminous United States) consists of the 48 adjoining U.S. states and the Federal District of the United States of America. The term excludes the only two non-contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii ...

. On March 12, 2019, the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act

The John D. Dingell Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act of 2019 is an Omnibus bill, omnibus lands act that protected public lands and modified management provisions. The bill designated more than of National Wilderness Preservation ...

added to the park.

Many of the larger cities and towns within the boundary of the regional groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in rock and soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. About 30 percent of all readily available freshwater in the world is groundwater. A unit of rock or an unconsolidate ...

flow system that the park and its plants and animals rely upon are experiencing some of the fastest growth rates of any place in the United States. Notable examples within a radius of Death Valley National Park include Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

and Pahrump, Nevada

Pahrump ( ) is an unincorporated town located at the southernmost tip of Nye County, Nevada, United States, about west of Las Vegas, Nevada. Pahrump lies adjacent to the Nevada–California border and the area had a population of 44,738 as of ...

. In the case of Las Vegas, the local Chamber of Commerce estimates that 6,000 people are moving to the city every month. Between 1985 and 1995, the population of the Las Vegas Valley increased from 550,700 to 1,138,800.

In 1977, parts of Death Valley were used by director George Lucas

George Walton Lucas Jr. (born May 14, 1944) is an American filmmaker. Lucas is best known for creating the ''Star Wars'' and ''Indiana Jones'' franchises and founding Lucasfilm, LucasArts, Industrial Light & Magic and THX. He served as chairm ...

as a filming location for ''Star Wars'', providing the setting for the fictional planet Tatooine

Tatooine () is a fictional desert planet that appears in the ''Star Wars'' franchise. It is a beige-colored, desolate world orbiting a pair of binary stars, and inhabited by human settlers and a variety of other life forms. The planet was first ...

.

Geologic history

The park has a diverse and complex geologic history. Since its formation, the area that comprises the park has experienced at least four major periods of extensive

The park has a diverse and complex geologic history. Since its formation, the area that comprises the park has experienced at least four major periods of extensive volcanism

Volcanism, vulcanism or volcanicity is the phenomenon of eruption of molten rock (magma) onto the surface of the Earth or a solid-surface planet or moon, where lava, pyroclastics, and volcanic gases erupt through a break in the surface called ...

, three or four periods of major sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to the ...

, and several intervals of major tectonic

Tectonics (; ) are the processes that control the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. These include the processes of mountain building, the growth and behavior of the strong, old cores of continents ...

deformation where the crust has been reshaped. Two periods of glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

(a series of ice ages) have also had effects on the area, although no glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s ever existed in the ranges now in the park.

Basement and Pahrump Group

Little is known about the history of the oldest exposedrock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

s in the area due to extensive metamorphism

Metamorphism is the transformation of existing rock (the protolith) to rock with a different mineral composition or texture. Metamorphism takes place at temperatures in excess of , and often also at elevated pressure or in the presence of chem ...

(alteration of rock by heat and pressure). Radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares t ...

gives an age of 1,700 million years for the metamorphism during the Proterozoic

The Proterozoic () is a geological eon spanning the time interval from 2500 to 538.8million years ago. It is the most recent part of the Precambrian "supereon". It is also the longest eon of the Earth's geologic time scale, and it is subdivided ...

. About 1,400 million years ago a mass of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

now in the Panamint Range intruded this complex. Uplift later exposed these rocks to nearly 500 million years of erosion.

The Proterozoic sedimentary formations of the Pahrump Group were deposited on these basement rocks. This occurred following uplift and erosion of any earlier sediments from the Proterozoic basement rocks. The Pahrump is composed of arkose conglomerate (quartz clasts in a concrete-like matrix) and mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from '' shale'' by its lack of fissility (parallel layering).Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology. ...

in its lower part, followed by dolomite Dolomite may refer to:

*Dolomite (mineral), a carbonate mineral

*Dolomite (rock), also known as dolostone, a sedimentary carbonate rock

*Dolomite, Alabama, United States, an unincorporated community

*Dolomite, California, United States, an unincor ...

from carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate g ...

banks topped by algal mat

Algal mats are one of many types of microbial mat that forms on the surface of water or rocks. They are typically composed of blue-green cyanobacteria and sediments. Formation occurs when alternating layers of blue-green bacteria and sediments ar ...

s as stromatolite

Stromatolites () or stromatoliths () are layered sedimentary formations (microbialite) that are created mainly by photosynthetic microorganisms such as cyanobacteria, sulfate-reducing bacteria, and Pseudomonadota (formerly proteobacteria). The ...

s, and finished with basin-filling sediment derived from the above, including possible glacial till

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

from the hypothesized Snowball Earth glaciation. The very youngest rocks in the Pahrump Group are basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic lava flows.

Rifting and deposition

A

A rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics.

Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-grabe ...

opened and subsequently flooded the region as part of the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the unit of geologic time from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago.

It is the last era of the Precambrian Supereon and the Proterozoic Eon; it is subdivided into the Tonian, Cryogenian, and Ediacaran periods. It is ...

(by about 755 million years ago) and the creation of the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. A shoreline similar to the present Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

margin of the United States lay to the east. An algal mat

Algal mats are one of many types of microbial mat that forms on the surface of water or rocks. They are typically composed of blue-green cyanobacteria and sediments. Formation occurs when alternating layers of blue-green bacteria and sediments ar ...

-covered carbonate bank was deposited, forming the Noonday Dolomite. Subsidence of the region occurred as the continental crust

Continental crust is the layer of igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rocks that forms the geological continents and the areas of shallow seabed close to their shores, known as continental shelves. This layer is sometimes called ''sial'' be ...

thinned and the newly formed Pacific widened, forming the Ibex Formation. An angular unconformity

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval o ...

(an uneven gap in the geologic record) followed.

A true ocean basin

In hydrology, an oceanic basin (or ocean basin) is anywhere on Earth that is covered by seawater. Geologically, ocean basins are large geologic basins that are below sea level.

Most commonly the ocean is divided into basins fol ...

developed to the west, breaking all the earlier formations along a steep front. A wedge of clastic sediment then began to accumulate at the base of the two underwater precipices, starting the formation of opposing continental shelves. Three formations developed from sediment that accumulated on the wedge. The region's first known fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s of complex life are found in the resulting formations. Notable among these are the Ediacara fauna and trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three lobes") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Trilobites form one of the earliest-known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the At ...

s, the evolution of the latter being part of the Cambrian Explosion

The Cambrian explosion, Cambrian radiation, Cambrian diversification, or the Biological Big Bang refers to an interval of time approximately in the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla started appearing in the fossil recor ...

of life.

The sandy mudflats gave way about 550 million years ago to a carbonate platform (similar to the one around the present-day Bahama

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the arch ...

s), which lasted for the next 300 million years of Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ' ...

time (refer to the middle of the timescale image). Death Valley's position was then within ten or twenty degrees of the Paleozoic equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

. Thick beds of carbonate-rich sediments were periodically interrupted by periods of emergence. Although details of geography varied during this immense interval of time, a north-northeastern coastline trend generally ran from Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

up through Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. The resulting eight formations and one group are thick and underlay much of the Cottonwood, Funeral, Grapevine, and Panamint ranges.

Compression and uplift

In the early-to-mid-

In the early-to-mid- Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceo ...

the western edge of the North American continent was pushed against the oceanic plate under the Pacific Ocean, creating a subduction zone. A subduction zone is a type of contact between different crustal plates where heavier crust slides below lighter crust. Erupting volcanoes and uplifting mountains were created as a result, and the coastline was pushed to the west. The Sierran Arc started to form to the northwest from heat and pressure generated from subduction, and compressive forces caused thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s to develop.

A long period of uplift and erosion was concurrent with and followed the above events, creating a major unconformity, which is a large gap in the geologic record. Sediments worn off the Death Valley region were carried both east and west by wind and water. No Jurassic- to Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

-aged sedimentary formations exist in the area, except for some possibly Jurassic-age volcanic rock

Volcanic rock (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) is a rock formed from lava erupted from a volcano. In other words, it differs from other igneous rock by being of volcanic origin. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic r ...

s (see the top of the timescale image).

Stretching and lakes

Basin and Range

Basin and range topography is characterized by alternating parallel mountain ranges and valleys. It is a result of crustal extension due to mantle upwelling, gravitational collapse, crustal thickening, or relaxation of confining stresses. The e ...

-associated stretching of large parts of crust below southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico started around 16 million years ago and the region is still spreading. This stretching began to affect the Death and Panamint valleys area by 3 million years ago. Before this, rocks now in the Panamint Range were on top of rocks that would become the Black Mountains and the Cottonwood Mountains. Lateral and vertical transport of these blocks was accomplished by movement on normal faults. Right-lateral movement along strike-slip faults that run parallel to and at the base of the ranges also helped to develop the area. Torsional forces, probably associated with northwesterly movement of the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and Iza ...

along the San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that extends roughly through California. It forms the tectonics, tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, and its motion is Fault (geology)#Strike-slip fau ...

(west of the region), is responsible for the lateral movement.

Igneous activity associated with this stretching occurred from 12 million to 4 million years ago. Sedimentation is concentrated in valleys (basins) from material eroded from adjacent ranges. The amount of sediment deposited has roughly kept up with this subsidence, resulting in the retention of more or less the same valley floor elevation over time.

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

ice ages started 2 million years ago, and melt from alpine glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s on the nearby Sierra Nevada Mountains fed a series of lakes that filled Death and Panamint valleys and surrounding basins (see the top of the timescale image). The lake that filled Death Valley was the last of a chain of lakes fed by the Amargosa and Mojave River

The Mojave River is an intermittent river in the eastern San Bernardino Mountains and the Mojave Desert in San Bernardino County, California, United States. Most of its flow is underground, while its surface channels remain dry most of the time, ...

s, and possibly also the Owens River

The Owens River is a river in eastern California in the United States, approximately long.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed March 17, 2011, It drains into and through the ...

. The large lake that covered much of Death Valley's floor, which geologists call Lake Manly

Lake Manly was a pluvial lake in Death Valley, California, covering much of Death Valley with a surface area of during the so-called "Blackwelder stand". Water levels varied through its history, and the chronology is further complicated by act ...

, started to dry up 10,500 years ago. Salt pans and playas were created as ice age glaciers retreated, thus drastically reducing the lakes' water source. Only faint shorelines are left.

Biology

Habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

varies from salt pan at below sea level to the sub-alpine conditions found on the summit of Telescope Peak, which rises to . NPS website, "Plants" Vegetation zones include creosote bush

''Larrea tridentata'', called creosote bush and greasewood as a plant, chaparral as a medicinal herb, and ''gobernadora'' (Spanish for "governess") in Mexico, due to its ability to secure more water by inhibiting the growth of nearby plants. In S ...

, desert holly, and mesquite

Mesquite is a common name for several plants in the genus ''Prosopis'', which contains over 40 species of small leguminous trees. They are native to dry areas in the Americas.

They have extremely long roots to seek water from very far under grou ...

at the lower elevations and sage

Sage or SAGE may refer to:

Plants

* ''Salvia officinalis'', common sage, a small evergreen subshrub used as a culinary herb

** Lamiaceae, a family of flowering plants commonly known as the mint or deadnettle or sage family

** ''Salvia'', a large ...

up through shadscale

''Atriplex confertifolia'', the shadscale or spiny saltbush, is a species of evergreen shrub in the family Amaranthaceae, which is native to the western United States and northern Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Me ...

, blackbrush

''Coleogyne ramosissima'' or blackbrush, is a low lying, dark grayish-green, aromatic,Turner, Raymond M. 1982. Great Basin desertscrub. In: Brown, David E., ed. Biotic communities of the American Southwest--United States and Mexico. Desert Plan ...

, Joshua tree

''Yucca brevifolia'' is a plant species belonging to the genus ''Yucca''. It is tree-like in habit, which is reflected in its common names: Joshua tree, yucca palm, tree yucca, and palm tree yucca.

This monocotyledonous tree is native to the ar ...

, pinyon-juniper

Junipers are coniferous trees and shrubs in the genus ''Juniperus'' () of the cypress family Cupressaceae. Depending on the taxonomy, between 50 and 67 species of junipers are widely distributed throughout the Northern Hemisphere, from the Arcti ...

, to limber pine

''Pinus flexilis'', the limber pine, is a species of pine tree-the family Pinaceae that occurs in the mountains of the Western United States, Mexico, and Canada. It is also called Rocky Mountain white pine.

A limber pine in Eagle Cap Wildernes ...

and bristlecone pine

The term bristlecone pine covers three species of pine tree (family Pinaceae, genus ''Pinus

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. T ...

woodlands. The salt pan is devoid of vegetation, and the rest of the valley floor and lower slopes have sparse cover, although where water is available, an abundance of vegetation is usually present.

These zones and the adjacent desert support a variety of wildlife species